I haven't seen

RoboCop since I was a kid, and then only on crappy dubbed and scrubbed TV broadcasts, so it was practically like I hadn't seen the film at all. Since my recent experience with the sublime

Black Book tipped me off that there's more to Paul Verhoeven than I expected, I figured it was about time to revisit this old classic. And I'm very glad I did. There's a lot going on in this film beyond its surface-level ultra-violent action, although of course the action is great and there's plenty of it. Verhoeven's wry, satirical perspective elevates what might have been a typical 80s schlock-fest into an enduring classic, a portrait of creeping totalitarianism at work. The titular RoboCop is actually Murphy (Peter Weller), a cop who has a fatal run-in with a group of notorious cop-killing drug-dealers. His body is then used as fodder by the corporation OCP, a Halliburton-like independent contractor that's taken over management of the Detroit police force in addition to their usual line of supplying military weaponry. OCP transforms Murphy into RoboCop, a wholly prosthetic cyborg with only trace memories of his old life, suppressed by the rigorous programming by which the corporation's scientists attempted to transform him into the "perfect" cop: dedicated to the letter of the law but without any emotions to interfere with its application. This is a frightening proposition, the idea that the perfect cop should be almost inhuman, but what's even scarier is that RoboCop is himself an improvement on the company's

other idea of the perfect cop, a robot with absolutely no human elements who winds up accidentally killing a senior manager due to a glitch. The film posits a conflict between the inhuman and the marginally more human, and forces the audience to root for the rigid RoboCop simply because he at least shows traces of his former humanity.

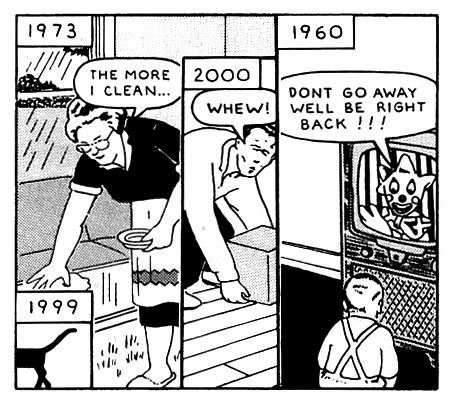

Within this story, Verhoeven works mostly with the small touches, especially the not-so-subtle media commentary contained in the frequent glimpses of television news and unfunny comedy shows. The recurring shots of a bizarre sitcom where the pervy main character has the catch phrase "I'll buy that for a dollar" are a riot, skewering the inanity of pop culture with total believability. Does anyone think that

couldn't be a real TV show? Even more pointed are the TV news clips, in which constantly smiling drones recite both tragic and ridiculous news with equal dismissiveness and flippancy. More subtly, these news blurbs provide hints of the darker subtexts at work in the culture, particularly the insinuation that the nation's current president is using an orbiting missile defense satellite as a base to kill his political enemies with controlled laser blasts, positioned in the media as "accidents." It's both hilarious and terrifying to see the grinning news anchors describe the laser-triggered explosions as accidental, while the graphic in the corner of the screen seems to indicate perfectly targeted shots at diverse locations. This kind of detail, almost subliminal at times, is packed into the margins of the film, suggesting the very scary and dystopian world that could both create RoboCop and decide that he's a desirable solution to its problems.

What's equally striking about

RoboCop is the extent to which it's actually a dark comedy rather than a straightforward action flick. Many of the scenes that should play out as action showcases wind up being really funny, especially the scene where RoboCop first battles it out with the ED-209 military droid that preceded him. This robotic battle machine is equipped with an animalistic growl, presumably to intimidate criminals, but it is apparently not programmed to be able to climb stairs, and RoboCop manages to elude it by simply running down a staircase. The robot then tentatively tries to follow — and the scene where it tests out the stairs with its ill-eqiuipped feet surprisingly anthropomorphizes it — but winds up on its back, squealing and crying like a baby and banging its legs on the floor in a robotic tantrum. The film also boasts a scenery-chewing parade of stock villains, including Kurtwood Smith as their sociopathic leader and pre-

Twin Peaks turns from both Miguel Ferrer (sleazy and leering as ever) and a gleefully creepy Ray Wise.

Although much of the film is as over-the-top as one would expect, there are moments of quiet empathy in which RoboCop's slow process of discovering his past is documented with real warmth and pathos. This is, amidst all the bluster and explosions, a very sad character, a man who died and left behind his beloved wife and child, but whose consciousness nonetheless continues to exist in some perfunctory form, trapped in the guts of a robotic shell. The scene where he explores his abandoned former house, now up for sale by an annoying real estate agent who appears only on TV monitors, is beautifully handled, as RoboCop's tour of the house triggers poignant memories from his past. Verhoeven manages to dig deep into a story that in other hands would require only numerous clichés and lots of blood splatter. The result is a film that isn't stingy with the expected blood — in fact, it's sometimes shockingly gory — but which also searches for multiple layers of meaning within RoboCop's story: not only political and social commentary, but addressing the question of what it is to be human and what separates a feeling human consciousness from a machine.

Georges Bizet's classic opera

Carmen is a primal tale, a story that's been told and retold, its elements rearranged and cast into different contexts, time and time again in various media and forms. This version,

Carmen Jones, is a distinctly American slant on the tale, directed by Otto Preminger based on the successful Broadway play, and populated by an all-black cast. It's a hugely promising premise, especially with Dorothy Dandridge as Carmen as Harry Belafonte as her luckless beau Joe. The leads have just the right chemistry and smoldering sexuality to infuse this

Carmen adaptation with raw energy and sensual sizzle whenever they're on screen. This version relocates the story to a Southern military base, where Joe is a soldier about to leave for flying school, and planning to marry his longtime sweetheart Cindy Lou (Olga James) before he leaves. But he's sidetracked by an assignment to bring the tempestuous Carmen, who has set her sights on him, to the local jail after she gets into a vicious fight with another woman. This detour quickly ends with Joe and Carmen in bed together, triggering the beginning of a stormy romance that leads the pair to Chicago, on the run with Joe AWOL from the military after fighting with an officer, where Carmen promptly deserts him for a prizefighter (Joe Adams) who likes to throw his money around freely.

It's a familiar story, and its archetypal quality is exactly its appeal. It casts the virgin against the whore, the small-town girl against the worldly wild woman, and nothing sums it up better than the saccharine song Joe sings to Cindy Lou shortly before he leaves her, praising her because she's just like his mom (hello, Oedipus!). Much has been made of the change of context from Spain to black America, but in point of fact it doesn't make much of a difference to the story, which plays out the same way no matter where it's set (as Godard proved, perhaps definitively, with his abstracted version of the story in

Prénom: Carmen). There's not much specifically black or specifically American about this story or its treatment here, other than the window dressing of the scenery and the characters' surroundings and occupations. And the music, taken directly from the Broadway play with Oscar Hammerstein's lyrics, is often awkwardly shoehorned into these surroundings, usually falling flat and fizzling even as the characters themselves are sizzling.

The main problem is that the music simply lacks the sexual charge contained in the performances by Dandridge and Belafonte, which drastically hampers the film whenever the characters start bursting into song. In the scene set at Pastor's Cafe, where one of Carmen's friends (Pearl Bailey) sings "Beat Out Dat Rhythm on a Drum," everything about the song's lyrics and the jitterbugging dancers in the background suggests a wild party, but the music is curiously tepid once it dispenses with an opening drum solo. And although the drummer is present in the background throughout the scene, and though the song explicitly calls for wild, rhythmic party music, the orchestrations are as flat and sickly as can be, a wan string section with no trace of the frantic drum beat that the drummer can be seen beating out on his kit. This curious lack of synchronization in the music carries through to the whole film, and even Belafonte and Dandridge get their voices dubbed by trained opera singers for the songs. The result is a near total disconnection between the music and the drama of the story, so that the music seems to be happening on a whole other plane, often sounding like it's being beamed in with no relation to the characters supposedly singing it. There's no trace of the sexual urgency that the leads bring to the film, no trace of the raw emotionality and desperation in every second of their performances — Carmen's fierce independence and fickle love, Joe's increasingly angry lust, even Cindy Lou's pathetic yearning for the man who pushed her aside. The weak and disconnected performances of the songs drain all this emotional fervor from the soundtrack, leaving it to the spoken portions of the film to get across the urgency of the narrative.

Of course, whenever the music stops, there are plenty of effective moments, especially in the film's second half. Dandridge is responsible for much of what's best in this film, and her loose, sexy performance can only be gawked at. When she stretches out her long bare legs towards Joe, huskily telling him to "blow on 'em" to dry her toenail polish, it's an impossibly suggestive moment, one of the cinema's best love scenes. Her performance is filled out by many such details and moments, from the sneering way she holds her lips to the hip-swaying swagger of her walk to the distinctive drawl of her voice. She even manages to get across the film's best song, Carmen's anthem "Dat's Love," by the sheer energy of her grinning performance, as she lip-syncs the telling lyrics: "You go for me and I'm taboo/ But if you're hard to get I go for you/ And if I do, den you are through, boy/ My baby, dat's de end of you." This song, with its contagious melody, is perhaps the one exception to the unbearable flatness of much of the music, and Preminger is wise to keep returning to it throughout the film, its presence a constant reminder of Carmen's predatory outlook on love and desire. It returns as snatches of string melody, bits of sung lyrics, and most memorably, with Carmen whistling it throughout a scene with Joe as she preps to go out and visit the boxer who she's already decided to go for.

Preminger's

Carmen Jones is ultimately a bit of a disappointment, though the sheer chemistry and raw power of the leads is nearly enough to revive it when its lackluster incorporation of the music threatens to drag it down. It's an interesting film primarily for the performances of Dandridge and Belafonte, who electrify the screen so completely that it's easy to forget about anything else when they're on screen.

Lessons Of Darkness is one of my favorite Werner Herzog films, and probably the best example of his distinctive approach to the thin line between documentary and fiction. Nowhere in his filmography has his blurring of this line been more complete than in this terse, mysterious, and evocative film, made in Kuwait and Iraq shortly after the first Gulf War, in the immediate wake of the Iraqi army's destructive retreat from occupied Kuwait. But despite this setting, the film is almost stridently apolitical — aside from a pair of scenes in which Arab women describe the tortures of Saddam Hussein's regime — and ahistorical in its treatment of the war, the region it occurred in, and the world situation and events that caused it. None of this is within the purview of Herzog's art; he has never been a polemical filmmaker, or even a particularly political one, preferring to examine particular people and places and events in terms of their relationship to grand archetypes and ideas. He is a director of the grandiose and the large-scale, even if he most often finds these elements in the specific megalomanias of individual people.

In this case, though, man is almost entirely absent from the film, and certainly individual man. The film's only speaking characters, besides Herzog's stoic and, as the film progresses, increasingly sparse, narration, are the two Arab women already mentioned, and they are not even translated, as Herzog simply describes their stories in his own words. The film's other people are silent, mostly men working on extinguishing the oil fires that Iraqi soldiers lit in the aftermath of the war, and they are glimpsed usually from a distance, covered in thick layers of protective clothing and framed in silhouette against the towering blazes. This abstraction from the human elements of the story allows Herzog to transform this documentary into a kind of science-fiction narrative about an alien world, and right from the start his narration enforces this idea. Herzog's films have often stressed the absurdity and hostility of nature, and the ultimate extreme for him — one he has explored in several other films as well, most notably

Fata Morgana, this film's direct antecedent — is the idea that our planet is alien to its own inhabitants. To this end, he has captured some of the most stunning and strangely beautiful images imaginable: lakes of oil, towering blazes that fill the sky with black smoke, a desert strewn with bones and mysterious metal wreckage, strange machines completing inscrutable tasks in the midst of this hellish landscape. It's no accident that the film is divided into chapters with titles like "Satan's National Park," or that Herzog's voiceover quotes liberally from the Book of Revelations; this is an apocalyptic vision.

The emphasis, of course, is on vision, since once the introductory few chapters are over, Herzog's voiceover recedes more and more into silence, and the film is propelled simply by the overpowering strength of its visuals and the sweeping, operatic music that accompanies them. Herzog spends much of the film up in a helicopter, dodging in between plumes of smoke and swooping across reflective lakes of oil. These images are equal parts horrifying and awe-inspiring, and Herzog presents them with a straightforward sensibility that lingers on each image, the camera slowly panning around these fiery infernos and giving the film a leisurely, contemplative pace. On the ground level, Herzog spends one entire chapter (the film's shortest but perhaps best) down at eye level with a large pool of oil that is bubbling in the heat. The dancing, bouncing droplets of oil, percolating with rhythmic pops, are like visual music, and the only sounds are the pops and burbling provided by the heated oil as it froths and spits up protuberances from the ground. Elsewhere, the film spends time with the men who are trying to extinguish the blazes, and Herzog treats these men as alien creatures, swaddled in thick protective suits and acting in mysterious and inexplicable ways, as when they re-ignite several oil plumes that had been put out.

It's perhaps impossible to overstate the unsettling beauty that Herzog has achieved here. In many ways, it's a very pure beauty, with every trace of political context effectively drained from the situations being depicted. Herzog has, of course, been criticized for this, but specific political engagement is not his style, and in any case there is something much deeper at work in this film, beyond the specific political events it is depicting.

Lessons Of Darkness is, rather than a commentary on the first Gulf War, an impassioned meditation on the fallout of

any war, a chronicle of the ways in which man's extreme violence has made nature itself alien to us. On the alien planet encountered in this film, a horrific war has set the ground against the planet's inhabitants, has ravaged the surface so thoroughly that it is engulfed in flames. Herzog finds an awesome beauty in these images, but also a profound sadness, a sense that we can never experience the world as our natural habitat, that it will always be strange and hostile to us because of the ways in which we uneasily coexist with it. Nature, for Herzog, is both beautiful and scary, and the same holds true for the works of man.