Abbas Kiarostami's Close-Up is a marvelously compelling documentary that, in the process of following the trial of a poor man accused of fraud, winds up delving into the nature of art and the relationship between fiction and deceit. The film is built around a real incident, the case of Hossain Sabzian, who impersonated the famous Iranian director Mohsen Makhmalbaf in order to ingratiate himself with the Ahankhah family, pretending that he was going to film a movie in their home with the family as actors. The family was initially trusting but came to suspect him more and more, finally exposing him by inviting over a friend of a friend, the journalist Hossain Farazmand, who knew the real director by sight and instantly recognized that Sabzian was a fraud. Kiarostami's film is partially a documentary of the resulting trial, and partially a reconstruction — using the real participants in the events as actors, including Sabzian himself and the family he conned — of the events preceding Sabzian's arrest.

The film opens with a re-enactment of the reporter taking a taxi to the Ahankhah house to arrest Sabzian. Farazmand and the taxi driver sit in the front, while two soldiers sit in the back, and during this lengthy opening sequence the men chat casually, talking about the case they're going to deal with, about film, about journalism, and about incidents from Iranian history that happened in the areas they pass through. The conversation is casual and seems unrehearsed, though this is a re-enactment of the real events that led up to Sabzian's arrest. Once the cab arrives at the house, Farazmand goes inside, but Kiarostami's camera remains in the cab, observing as the driver chats amiably with the two soldiers in the back seat, asking them about their families and their homes. Then the soldiers go inside too, and again Kiarostami remains outside with the driver, as the man gets out of the car, picks up some flowers from a pile of trash, sniffs the flowers, and kicks an aerosol can so it rolls noisily down the street. The can rolls along the concrete, and Kiarostami's camera pans after it, eventually following it as the can starts to drag sideways across the ground in an unnatural movement, presumably pulled along by an unseen string from off-camera.

In this way, the subtle naturalism and observational aesthetic of the opening scenes gives way to a sense that things are being tweaked by the filmmakers, that not everything is necessarily as it seems. It's a reminder that the film's re-enactments are only playing at realism; they are in fact carefully arranged and scripted, based on real events but not in themselves "real" or unmediated. The naturalism of the opening is further deconstructed when, after Sabzian's arrest, the reporter remains behind, frantically running from door to door in the neighborhood to ask to borrow a tape recorder. The scene is farcical and surreal, as Farazmand rings doorbells at random, introduces himself, and asks for a tape recorder. One starts to wonder what kind of reporter shows up for a big story like this, planning to do an interview, and then has to beg for a tape recorder from complete strangers. It's comical and strange, especially when Farazmand finally gets his tape recorder and goes scurrying off down the street, pausing just once to give the aerosol can lying in the road a savage kick that sends it flying into the air, coming down and once again rolling along as the reporter disappears down a side street. As the credits finally roll, ushering in the meat of the subsequent film, concerning Sabzian's trial, Kiarostami leaves the audience to wonder about this strangely unprepared reporter, about con men, about reportage, about lies and fictions.

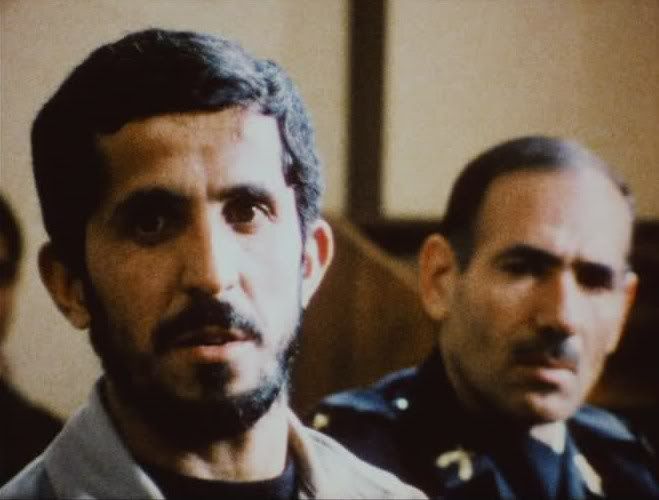

The images of the trial itself, captured in grainy footage that contrasts against the crisp, clean images of the re-enactments, are focused on Sabzian and his explanations for what he did. Kiarostami had remarkable access in the surprisingly relaxed courtroom where the trial takes place — or else not all of the trial footage is genuine, which only further blurs the film's interesting perspective on reality versus fiction, truth versus lies. Kiarostami seems too involved, too active in the trial's progress, for all of this footage to be real, unless Iranian courts are significantly less controlled than Western courts. The judge sits across the room, asking questions of Sabzian and the Ahankhah family, but for the most part Kiarostami's camera remains focused on Sabzian's face. At the beginning of the trial, Kiarostami explains to the defendant that this camera has a close-up lens and will remain trained on Sabzian, to capture his reactions and to provide him with a way to speak his mind and make his ideas clear. Kiarostami is making explicit what this film is about: he wants to give Sabzian an opportunity to express himself, to help others understand why he did what he did. During the trial, Kiarostami frequently even intervenes (or seems to intervene) in the proceedings himself, asking Sabzian direct questions and prompting the defendant to speak at length about the feelings and ideas that were behind his actions.

These close-ups of Sabzian are astonishingly moving, especially since the defendant's words reveal that he was no simple con man, that he was not trying to bilk the family out of money or otherwise exploit them. He did what he did, he says, because it made him feel respected. He is a poor man, divorced from his wife because of his inability to provide for his family very well, and he still struggles, constantly in and out of work, living a very poor and simple life with few real pleasures. His only pleasure, it seems, is the stimulation provided by the cinema, by art: he goes to the movies, especially the movies of Makhmalbaf, and finds a voice dealing with the kind of "suffering" that he himself feels in his own life. He is especially moved by the director's film The Cyclist, about which he says, "It says the things I wish I could express." With Kiarostami's prodding, the trial becomes a discourse on the purpose of art, the ways in which art can reach into people's lives in surprising ways. It becomes obvious that Sabzian impersonated Makhmalbaf because he wanted to feel as though he could reach people in that way, that he could express the things he feels with such clarity and beauty. As he struggles to express himself, to explain his actions, the subtext is the idea that art communicates. Sabzian's halting but often poetic descriptions of his "suffering," his poverty and feelings of uselessness and desperation, are a form of art, shaped and crafted by Kiarostami in turn.

The film is not only a commentary on the purpose of art but a subtle piece of social commentary as well, suggesting the hopelessness of poverty and unemployment that affects so many people. Even the Ahankhah family, who seem reasonably well-off in their large house, are not unaffected, as they have two sons who went to school for engineering, only to find that neither of them could get a job in the field after graduation. Instead, one son works in a bakery and the other is still unemployed. Sabzian's inconsistent work and constant struggles with money are even more extreme, and in court one of the Ahankhah sons, forgiving the defendant at the end of the trial, says that he blames "social malaise and unemployment" for Sabzian's actions. Kiarostami doesn't draw quite that straight a line between cause and effect, but it's obvious that he too thinks that this odd story is at least partially about class and economic hardship. Sabzian didn't commit his crime for money, even though he did borrow some money from the family at one point. He wanted to be Makhmalbaf not to get money, but in order to escape from his pathetic real life. He was playing a part and relishing the attention and respect he earned from the family who believed him to be a famous artist.

As he says himself at the end of the trial, at Kiarostami's prompting, he was more of an actor than a director, though. He was playing a part, he says repeatedly, and the structure of Kiarostami's film reinforces the connection between lying and acting, between the art of fiction and the art of the con man. The re-enactments in Close-Up, bringing together the real participants in these events to play out their scenes again, insert a further layer of fiction and artifice. In the reconstructions, Sabzian is playing at playing, pretending to pretend, while the rest of the actors are engaged in the same deceit. They play at reality, staging seemingly casual conversations that in fact are anything but unmediated. It is the flipside of the film's idea that art can reveal truths and speak to people about their own lives: art is also lying and pretending, and in that sense Kiarostami's film makes a very moving, strangely beautiful artist of Hossain Sabzian.

11 comments:

This post is at least the fourth/fifth time Kiarostami's name cross my daily web life in a few weeks. I take it as a sign to finally approach this director. Thanks.

Hah, yeah, I've finally checked out his work only recently myself. I'm glad I did!

I was just going to watch this the other night and unfortunately didn't get to. I'm quite embarassed actually, as an Iranian and a Kiarostami enthusiast, that I've never seen Close-Up.

But to add to Gekko's point, I'm really happy for this newly increased exposure to his work. He was more or less forgotten in the 2000s until Certified Copy, but I'm happy people are checking his older films out.

Fantastic review, Ed. This very well may be my favorite Kiarostami, a beautiful & complex masterpiece. Perhaps only Pedro Costa since has so tantalizingly blurred the lines between fiction and reality. I'm glad you point out that we are never quite sure whether the trial footage is real or not, and likewise we don't know to what degree Kiarostami orchestrated the powerful, climactic meeting, whether or not the audio glitches in that scene are fabricated, etc. The constant uncertainty on the viewers part of where exactly the line is drawn between the artifice and the actuality gives the whole experience such a unique, edgy aura.

Sabzian is such a fascinating, tragic figure. There is an extra on the Criterion disc that catches up with the man some years after the film was made, and it is pretty haunting stuff. IIRC, it appeared as though he enjoyed his newfound fame/notoriety from the film for a brief period before plunging even harder back down into his well of depression and solipsism. I think he died not too long after.

It's definitely a fascinating film, but a fascinating film in so many unconventional ways that I find it hard to make heads or tails of what I'm thinking. It's almost as if someone else is thinking these things and I'm overhearing their thoughts while holding my own thoughts which they are simultaneously weighing in on. In fact, that is the exact sensation. The most befuddling part is how seemingly oblivious the imposter is to the whole situation. And, of course, that's probably the explanation for the situation, but it seems like this obliviousness is at the core of everything - beyond fact and beyond fiction there is this man who is oblivious to both, and only through this can he embody fiction and reality with the same oblivious stare which renders both irrelevant, since you couldn't pull him one way or the other. On top of this is Kiarostami's own sly form of obliviousness, although maybe he seems more sly and less oblivious when watched on blu-ray rather than a fuzzy DVD copy. It's the perfect counterpoint to Certified Copy - he acts as if he is a copy of someone else but doesn't even seem to succeed at being a copy of himself when he's supposed to be. But then perhaps I give Kiarostami too little credit. I blame the blurriness. He's a sly fox. Probably getting more sly with age. Kind of excited to see where he goes next. And previous, for that matter.

Thanks, Amir. I need to see more Kiarostami myself, I look forward to exploring more of his work.

Drew, yes there are so many provocative ways in which the line between reality and artifice are blurred here. I found the sound-cutting-out device at the end thoroughly unconvincing, and didn't believe for a moment that it was real - but maybe it was, after all truth can be stranger than fiction. There's always that doubt even when something seems totally staged, like Sabzian buying the flowers and that whole sequence in general. It's great stuff.

A shame about the real Sabzian - I heard that he died but it's sad that he didn't really capitalize on the opportunity to make a new life after this movie.

Jean, Kiarostami "oblivious"? I'm not sure what you mean by that: it seems to be that the various confusions and manipulations of this film are very deliberate, and that it should be puzzling and disconcerting in its effect. That's a big part of what makes it so great to me. It's not at all obvious what one is supposed to think at any given moment. I think Kiarostami, despite the appearance of disorder (an appearance he very much wants to cultivate), is definitely aiming for that productive confusion that generates multiple conflicting thoughts and emotions.

"The film is not only a commentary on the purpose of art but a subtle piece of social commentary as well, suggesting the hopelessness of poverty and unemployment that affects so many people."

Your opening sentence and this subsequent observation frame this film perfectly. This is one Kiarostami's most celebtaed works, standing as it does alongside A TASTE OF CHERRY and THE WIND WILL CARRY US among this artists's masterpieces. The roving camera and the taxi cab conversations are trademark devices of this artist, and as you well denote they serve as the narrative foundation to affect that blurred perspective.

CLOSE-UP is certainly a commentary on post-revolutionary Iranian society, where individual aspirations are subject to painful lessons of a system that has more than it's share of failings and frustrated. This wrenchingly humanist film as everyone knows here is available now on a stunning Criterion blu-ray, with a wonderful commentary track led by Jonathan Rosenbaum:

http://www.amazon.com/Close-Up-Criterion-Collection-Mohsen-Makhmalbaf/dp/B003E0YU04/ref=sr_1_1?s=dvd&ie=UTF8&qid=1308060969&sr=1-1

Thanks, Sam. Yes, this is a powerful commentary on Iran in the post-revolutionary period, as the tone of the opening conversations, in which the men discuss events that happened during the revolution, makes clear.

The Criterion DVD is great (the blu-ray too, I'm sure) and even includes the entirety of Kiarostami's fine early feature The Traveler as a bonus.

I love your blog. Thanks for exposing me to films I'd otherwise never know about; great writing, too.

i love your blog. for someone "new to kiarostami" your critique is incisive and quite compelling.

Post a Comment